6 Month Report

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Further Information:

6 Month Report – Detailed Version

|

|

Introduction to Six Month Report |

The intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic inequalities in children’s health and cognitive, behavioural, and emotional development emerge early and can persist through life (Najman et al., 2004; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

The intergenerational transmission of socioeconomic inequalities in children’s health and cognitive, behavioural, and emotional development emerge early and can persist through life (Najman et al., 2004; Shonkoff & Phillips, 2000).

Evidence suggests that targeted, early intervention programmes aimed at disadvantaged children and their families are an effective means of reducing these inequalities.

Preparing for Life (PFL) is a prevention and early intervention programme which aims to improve the life outcomes of children and families living in North Dublin, Ireland. The programme is being evaluated by the UCD Geary Institute and this evaluation aims to provide evidence on the effectiveness of such early interventions. This chapter describes the objectives and theoretical rationale of the PFL Programme and Evaluation, as well as the aims and structure of the report.

|

|

The PFL Evaluation |

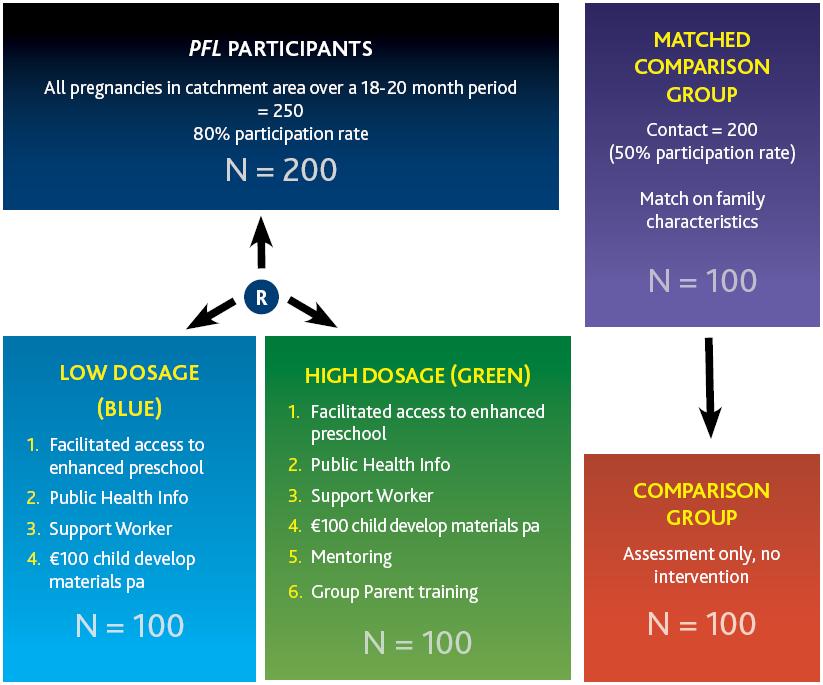

The PFL Programme is being evaluated using a mixed methods approach, incorporating a longitudinal randomised control trial design and an implementation analysis. The experimental component involves the random allocation of participants from the PFL communities to either a high support treatment group or a low support treatment group. Both groups receive developmental toys, facilitated access to preschool, public health workshops, and have access to a support worker. Participants in the high treatment group also receive home visits from a trained mentor and group parent training using the Triple P Positive Parenting Programme. The PFL treatment groups are also being compared to a ‘services as usual’ comparison group (LFP), who do not receive the PFL Programme.

|

|

Recruitment & Baseline Analysis |

In total, 233 pregnant women were recruited into the PFL Programme between January 2008 and August 2010. Randomisation resulted in 115 participants assigned to the high treatment group and 118 participants assigned to the low treatment group. In addition, 99 pregnant women were recruited into the comparison group. The population based recruitment rate was 52%. Baseline data, collected before the programme began, was available for 104 and 101 high and low PFL treatment group participants respectively, and 99 comparison group participants. Tests of baseline differences between the high and low PFL treatment groups found that the two groups did not statistically differ on 97% of the measures analysed, indicating that the randomisation process was successful. The aggregate PFL group and the LFP comparison group did not statistically differ on 75% of the measures; however, the comparison group was of a relatively higher socioeconomic status.

In total, 233 pregnant women were recruited into the PFL Programme between January 2008 and August 2010. Randomisation resulted in 115 participants assigned to the high treatment group and 118 participants assigned to the low treatment group. In addition, 99 pregnant women were recruited into the comparison group. The population based recruitment rate was 52%. Baseline data, collected before the programme began, was available for 104 and 101 high and low PFL treatment group participants respectively, and 99 comparison group participants. Tests of baseline differences between the high and low PFL treatment groups found that the two groups did not statistically differ on 97% of the measures analysed, indicating that the randomisation process was successful. The aggregate PFL group and the LFP comparison group did not statistically differ on 75% of the measures; however, the comparison group was of a relatively higher socioeconomic status.

|

|

Impact of PFL at Six Months: Main Results |

In total, 257 six month interviews (nLow = 90; nHigh = 83; nLFP = 84) were completed. The main results compared the six month outcomes of the high treatment group to the six month outcomes of the low treatment group across eight main domains: child development, child health, parenting, home environment and safety, maternal health and pregnancy, social support, childcare and service use, household factors and socioeconomic status (SES), incorporating 160 outcome measures. Consistent with the programme evaluation literature, there were limited significant differences observed between the high and low treatment groups at six months. However, many of the outcomes were in the hypothesized direction, with the high treatment group reporting somewhat better outcomes than the low treatment group. Of the

In total, 257 six month interviews (nLow = 90; nHigh = 83; nLFP = 84) were completed. The main results compared the six month outcomes of the high treatment group to the six month outcomes of the low treatment group across eight main domains: child development, child health, parenting, home environment and safety, maternal health and pregnancy, social support, childcare and service use, household factors and socioeconomic status (SES), incorporating 160 outcome measures. Consistent with the programme evaluation literature, there were limited significant differences observed between the high and low treatment groups at six months. However, many of the outcomes were in the hypothesized direction, with the high treatment group reporting somewhat better outcomes than the low treatment group. Of the

160 individual outcomes analysed, there were significant differences between the high and low treatment groups on 23 measures (14%). There were no significant effects in the domains of child development and household factors/SES. The domains with the most positive effects were social support, home environment and safety, and parenting. Specifically, children in the high treatment group compared to those in the low treatment group had more appropriate eating patterns, had a higher level of immunization rates, had more parental interactions, and parent-child interactions were of a higher quality. Additionally, children in the high treatment group were exposed to less parental hostility, a safer home environment, and more appropriate learning materials and childcare. Moreover, mothers in the high treatment group were more likely to be socially connected in their community and less likely to be hospitalized after birth. The results of the multiple hypotheses testing strengthen these findings by showing that the high treatment group reported higher scores on the quality of the home environment and in the domain of maternal physical health, and lower scores on parental stress compared to the low treatment group.

|

|

Interactions and Sub-group Results |

The interaction and sub-group analysis was conducted to determine whether the PFL programme had a varying impact on girls or boys, first time or non-first time mothers, lone or partnered parents, mothers with higher or lower cognitive resources, and families with high or low familial risk. The results indicated that the programme had differential impacts with some groups benefitting more from the programme than others. For example, there was suggestive evidence that the programme benefited mothers with relatively higher cognitive resources, mothers with multiple children, and families who have experienced familial risk.

|

|

Comparison Group Results |

As expected, the comparison of the six month outcomes of the two PFL treatment groups and the comparison group (LFP) found there were more significant differences in the outcomes of the high treatment group versus the comparison group than in the outcomes of the low treatment group versus the comparison group. Specifically, of the 151 individual outcomes analysed, there were positive significant differences between the high treatment group and the comparison group on 32 measures (21%), with most effects in the domains of social support, parenting and the home environment. A number of these effects remained significant in the multiple hypothesis analysis. In addition, there were positive significant differences between the low treatment group and the comparison group on 17 measures (11%), with most effects in the domains of social support, the home environment, and household factors/SES. However, very few of these effects remained significant in the multiple hypothesis analysis. Overall, the results of the high treatment group and comparison group analysis support the main findings, such that the additional supports provided to the high treatment group appeared to have some positive effects at six months, while the results of the low treatment group and comparison group analysis suggest that the low treatment is having a lesser impact on participant outcomes at six months.

|

|

Attrition at Six Months |

On average, 10% of the sample officially dropped out of the programme between the baseline assessment and six months (HIGH=13%, LOW=6%, LFP=10%) and 8% of the sample were classified as disengaged (HIGH=9%, LOW=10%, LFP=6%). Very few individual participant characteristics were associated with programme attrition and disengagement.

On average, 10% of the sample officially dropped out of the programme between the baseline assessment and six months (HIGH=13%, LOW=6%, LFP=10%) and 8% of the sample were classified as disengaged (HIGH=9%, LOW=10%, LFP=6%). Very few individual participant characteristics were associated with programme attrition and disengagement.

|

|

Dosage |

Families in the high treatment group received an average of 14 home visits by the PFL mentors between programme intake and six months, with each visit lasting about one hour on average. The frequency and duration of the visits did not differ significantly across the pre- and post-natal periods. The majority of participants reported meeting their mentor twice a month (68%). Few individual participant characteristics were associated with the frequency or duration of home visits. The only factors consistently associated with participant engagement were gestational age upon programme entry, cognitive resources, and vulnerable attachment style.

|

|

Satisfaction |

Overall participant satisfaction with the programme was high. As expected, the high treatment group reported greater satisfaction with the programme than the low treatment group. The high treatment group reported greatest satisfaction with having received the type of help they wanted, followed by satisfaction regarding the child’s progress and overall satisfaction with the programme. The low treatment group reported that they were most satisfied with the child’s progress and child behaviour.

|

|

Qualitative |

As part of the PFL process evaluation, focus groups were held with 23 programme participants and individual interviews were conducted with 7 PFL staff members. The findings from this qualitative analysis indicated that both participants and programme staff feel that the PFL programme is of benefit to families in the community. Both participants and staff cite several core factors that contribute to the programme’s perceived success. These include rapport between mentors and participants, respect for participant time, clear and concise informational materials, and the flexibility to meet participant needs within the PFL framework. Additionally, those in the high treatment group reported more benefits from the programme than did those in the low treatment group. This finding indicates high programme model fidelity.

|

|

Contamination |

A contamination analysis was conducted to determine whether the low treatment group received all or part of the additional services designed for the high treatment group. This analysis found that the potential for contamination was high as participants were in regular contact with each other and shared materials. However, direct measures of contamination suggest that these practices did not translate into improved parenting knowledge for those in the low treatment group. These findings indicate that the level of contamination in the PFL programme up to six months was quite low and does not bias the six-month results.

|

|

Six Month Report Summary & Conclusions |

The six month evaluation of Preparing for Life suggests that the programme is progressing well. Although, as found in other studies of home visiting programmes, there were limited significant differences reported between the high and low PFL treatment groups and the PFL treatment groups and the comparison group at six months. However, many of the relationships were in the hypothesized direction, with the high treatment group reporting somewhat better outcomes than the low treatment group. There were some significant findings in the domains of parenting, the quality of the home environment and social support across all groups, which correspond directly to information on the PFL Tip Sheets delivered to participants during this period. However, the programme had no significant impact on key factors such as pregnancy behaviour, infant birth weight, breastfeeding, and child development. In regards to implementation, attrition was relatively low during this period, yet the level of engagement was less than anticipated. Overall, participant satisfaction was high and the qualitative findings suggest that participants, most notably those in the high treatment group, found the programme enjoyable, informative and beneficial. One of the main findings to emerge from the quantitative analyses was that mothers with relatively higher cognitive resources received a greater number of home visits and may have benefited more from participation in the PFL programme overall. These findings will be investigated in more detail in later reports.

The six month evaluation of Preparing for Life suggests that the programme is progressing well. Although, as found in other studies of home visiting programmes, there were limited significant differences reported between the high and low PFL treatment groups and the PFL treatment groups and the comparison group at six months. However, many of the relationships were in the hypothesized direction, with the high treatment group reporting somewhat better outcomes than the low treatment group. There were some significant findings in the domains of parenting, the quality of the home environment and social support across all groups, which correspond directly to information on the PFL Tip Sheets delivered to participants during this period. However, the programme had no significant impact on key factors such as pregnancy behaviour, infant birth weight, breastfeeding, and child development. In regards to implementation, attrition was relatively low during this period, yet the level of engagement was less than anticipated. Overall, participant satisfaction was high and the qualitative findings suggest that participants, most notably those in the high treatment group, found the programme enjoyable, informative and beneficial. One of the main findings to emerge from the quantitative analyses was that mothers with relatively higher cognitive resources received a greater number of home visits and may have benefited more from participation in the PFL programme overall. These findings will be investigated in more detail in later reports.